Turkey Day

I WAS EIGHTEEN and home from college on Thanksgiving break. It was my mother’s birthday. John F. Kennedy had just been shot. And my father was being carried out on a stretcher.

“Don’t-let-her-see, keep-her-away,” I heard my two brothers shush as they lifted the stretcher. I froze, as if by remaining still, they would not see me see him: his arms strapped to his side, his elbows locked; his body bound in a straitjacket, then sunk in a stretcher like a furrow in a field; his eyes, the only part of his body not restrained. They couldn’t restrain his eyes: two black dots flickering in the light, darting wildly back and forth.

They carried him out the door and my mother followed, pausing in the doorframe. I watched her fling a kerchief over her head, tie a knot under her chin, then turn and ask me would-I-watch-the-turkey.

I nodded yes, I would watch the turkey, not TV.

A simple request, as if my mother were going on a quick run to the grocery store and would be right back, as if there would be a dinner, a feast, a celebration, as if the turkey would be eaten. But above her words, my mother’s eyes stared blankly. She couldn’t do a thing about it, none of it: Kennedy’s death right on TV for all the world to see or her husband’s breakdown for our eyes only.

I entered the doorframe and stood still as a still life, listening to the sound of the ambulance taking them away, no siren, the sound of tires rolling down the gravel driveway, fading into the distance.

I walked toward the muffled sound of TV in the living room, turned the sound off, and watched images of Kennedy’s body being carried into an ambulance played over and over as if no one could believe it.

The house fell silent except for an occasional hiss from the turkey roasting in the oven.

I sat on the gray kitchen linoleum, propped up against a cupboard next to the oven and waited.

I listened.

The turkey hissed and hissed.

When darkness fell suddenly like a curtain,

I tensed, lost in the dark,

frightened by the sizzling turkey sounding

closer and closer.

I must stay very still.

My breathing was too loud.

The doorbell rang, sending me into a state of ALARM

Who? Who? would come here now?

I hesitated, then decided I had better open the door. Perhaps it was important.

My friend Bob stood facing me. “What are you doing? I didn’t think anyone was home. Your house is all dark, no car in the drive. Where is everyone?”

“Something came up. They had to go out,” I said, keeping him in the doorframe.

“I just wanted to tell you that Tommy was coming for Christmas break.”

I looked at him blankly. The turkey hissed.

“Tommy, the guy from Maine you spent all summer with.” Instead of me, he didn’t say.

“Oh, that’s nice.”

“Nice?”

I nodded blankly. “I’ve-gotta-go-watch-the-turkey,” I blurted, easing the door toward him.

“Can I call you later?”

“Sure,” I replied, shutting the door, leaving him in the dark.

I heard the porch door shut, then turned and walked across the small kitchen past the gateleg table and sat back down on the gray linoleum floor in front of the oven. I hugged my knees and listened to the turkey hissing, hissing in the dark, hot oven, fat dripping like sweat from its headless body. Memory of my mother sewing a flap of skin over its neck cavity to keep the stuffing in. This dead turkey this day, my only companion.

My mother had asked me to watch the turkey, but I couldn’t see the turkey. I sat in the dark alone, so alone. There was no window for viewing. I opened the oven door and sat cross-legged watching the turkey. Then I turned off the oven. After a while, the turkey stopped hissing.

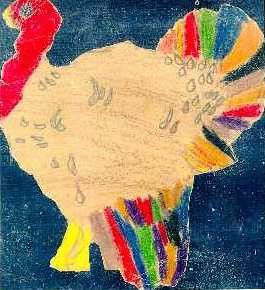

I remembered the turkey I had colored in second grade, each feather a different color, all its feathers spread like a peacock. A happy turkey. Not a turkey beheaded for the oven. And then I grew sad, so sad: my father, my mother, JFK, and the turkey, Turkey Day.